Problems with identity are something of a trend with horror movies. Dissociative Identity Disorder (DID) was originally thought to be sleepwalking: patients would switch between their normal consciousness and an unconscious state. However, after more observation of patients, it is observed that many patients had previously suffered traumatic experiences or nervous disorders, which had triggered their conditions. By knowing this information, Alfred Hitchcock’s 1960 Psycho, can be seen as a horrifying psychological tale of a man suffering from Dissociative Identity Disorder who runs a motel with his “mother.” Intentions of the villain Norman Bates can be studied by reading and being familiarized with “When the Woman Looks,” by Linda Williams and “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema,” by Laura Mulvey. Cinema offers a number of possible pleasures to viewers (Mulvey). Scopophilia serves as the most important pleasure regarding Psycho because of how Norman Bates stares at a woman through a hole in the wall, clearly fascinated by her form, and perceiving her as a erotic object.

The scene that viewers should study in order to get a good idea of psychological tension would be the conversation between Norman Bates and Marion Crane in Bate’s office parlor. Sharp dialog, mood swings, well executed camera angles and great character reactions fill the eerie mise en scene. The dialogue between Bates and Crane is sharp, and with analysis, viewers can pick up some of the hints that Bates leaves the audience with about his “mother.” A few examples include when Bates says to Crane, “My mother is …what’s the phrase… she isn’t quite herself today,” and “We all go a little mad sometimes.” These phrases, as well as how Bates stares at Crane during the scene, insinuates something far darker. Additionally, the camera angles should be noted as well. While Bates and Crane are speaking, the camera stays at eye level for both of the characters (Figure 1).

However, when Crane mentions anything about Bates’ mother, he gets very defensive and his moods changes instantly. Bates’ facial features become stand offish and he looks as if he wants to attack Crane. This can further be shown when the camera angle changes between the two characters during their conversation (Figure 2).

Bates is being viewed from a low angle. The audience is looking up at Bates. In the background is Bates’ stuffed owl with it’s wings spread in an attack position. At the same time, the viewers are seeing Marion at a downward angle. Bates has become the predator and Marion the prey. This is an interesting angle between Bates’ “male gaze” and Crane’s “female look” which can be analyzed using “When the woman looks,” by Linda Williams. For where the (male) voyeur’s properly distanced look safely masters the potential threat of the (female) body it views, the woman’s look of horror paralyzes her in such a way that distance is overcome; the monster or the freak’s own spectacular appearance holds her originally active, curious look in a trance-like passivity that allows him to master her through her look. At the same time, this look momentarily shifts the iconic center of the spectacle away from the woman to the monster (Williams). Even though Norman Bates looks as a regular man, his cold facial features and eerie body language quickly captivates Crane in a trance-like passivity that allows him to continue to objectify her, study her, and master her through his look.

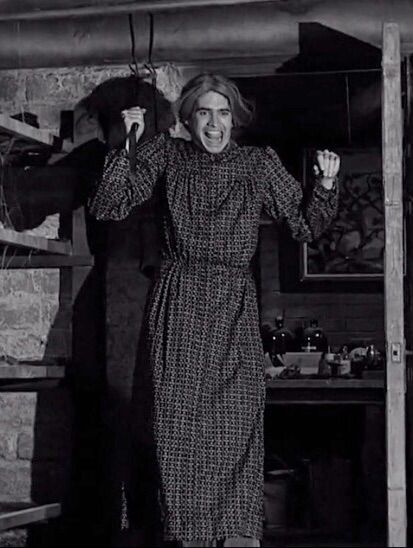

In the last few sequences of the film, viewers should take note of the lighting and how it portrays the chaos unfolding as well as how the woman’s gaze is punished for her curiosity. “The woman’s exercise of an active investigating gaze can only be simultaneous with her own victimization” (Williams). Crane’s sister, who was overly curious and zealous on wanting to find her sister Marion, found her way into the cellar of Norman Bates. The room was lit by one bulb that barely worked where Bates’ “mother” sits in a wheelchair. Crane’s sister touches the mother’s shoulder, the wheelchair swings around, revealing that it’s Bates’ mother’s corpse. Crane’s sister screams and draws her hand back hitting the light bulb, causing the bulb to swing back and forth. The result is an alternating light and shadow scene due to the bulb swaying back and forth: Crane’s sister’s terrified face, Bates’ mother’s corpse, Bates running into the cellar in mother’s clothes wielding a knife (Figure 3), a man running in behind Bates and dragging him to the floor, Bates’ face becoming an ecstasy of madness and despair as the knife falls to the floor and the wig slips from Bates’ head.

The film comes to a chilling ending with Norman Bates behind bars wrapped in a blanket, and saying in his mother’s voice, “Why, she wouldn’t even harm a fly.” The scene then fades into a shot of Marion’s car being dragged from the swamp Bates’ dumped it in. As Bates’ image disappears from the viewers, the face of mother’s corpse can be seen across Bates’ face for a fraction of a second. With that, Hitchcock’s Psycho is a horrifying psychological tale of a man suffering from Dissociative Identity Disorder who throughout the film gains pleasure in looking at another person as an erotic object, as well as sending a sinister message to women about what happens if they get too curious and have a look of their own compared to their male counterparts.